From pv magazine Global

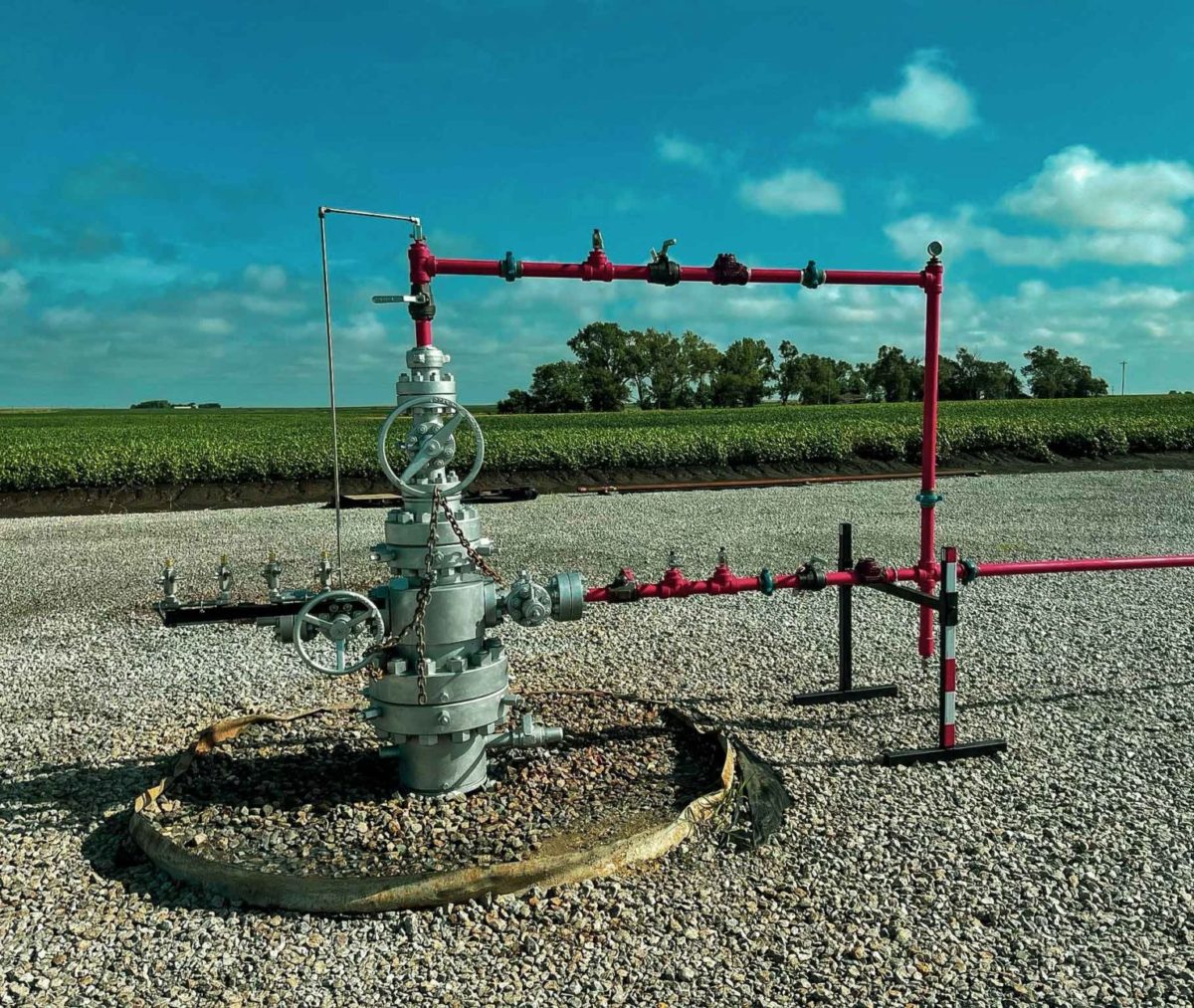

In April, the newly formed Western Australian company HyTerra announced plans to acquire 100% of Neutralysis Industries. Neutralysis, also Australian, holds a stake in an established Nebraska project alongside Natural Hydrogen Energy, a company with one of the field’s top researchers, Viacheslav Zgonnik, at its helm. The move would effectively be HyTerra’s “in,” giving it access to expertise, room to demonstrate, and a wellspring of naturally occurring hydrogen.

While the world has known for many decades about hydrogen accumulating under the earth’s surface, the phenomenon has largely been ignored. The main reason for that, HyTerra Business Development Manager Luke Velterop told pv magazine Australia, is simply because there’s previously been no market for it. Hydrogen is finicky to handle and in the past oil and gas have been considered just fine.

Now the urgent need to decarbonize has changed that, opening up new avenues of interest. In February, pv magazine reported that in the past year, exploration licenses amounting to one-third of South Australia’s total landmass have been either granted or applied for by companies in search of natural hydrogen.

As HyTerra Executive Director and Chief Technical Officer Avon McIntyre explains, it isn’t that South Australia is particularly bountiful in natural hydrogen accumulations, but simply that the state leads the country in terms of exploration regulations for the nascent industry. Accumulations, he says, may well be found all across Australia. And HyTerra and a handful of other companies are vying to secure them first.

Two mechanisms

While there remains some debate natural hydrogen, which has until now rarely been a focal point, there is consensus around the two main ways underground accumulations of the molecule develop.

The first, called “serpentinization,” is an underground reaction between iron and water. As McIntyre, who spent 13 years at Shell as an exploration geologist explains, the reaction occurs when water comes into contact with iron rich rocks below the atmospheric incursion level.

“Then those iron-rich rocks, they effectively want to rust, they want to turn into iron oxides … so they will strip the oxygen atom off the H2O and that releases the hydrogen,” McIntyre told pv magazine Australia. “This is a well understood process and people have known about it for many, many years. It’s just that nobody’s really considered if this could be an economically viable process.”

Authored by Bella Peacock

To continue reading, please visit our pv magazine Australia website.

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

By submitting this form you agree to pv magazine using your data for the purposes of publishing your comment.

Your personal data will only be disclosed or otherwise transmitted to third parties for the purposes of spam filtering or if this is necessary for technical maintenance of the website. Any other transfer to third parties will not take place unless this is justified on the basis of applicable data protection regulations or if pv magazine is legally obliged to do so.

You may revoke this consent at any time with effect for the future, in which case your personal data will be deleted immediately. Otherwise, your data will be deleted if pv magazine has processed your request or the purpose of data storage is fulfilled.

Further information on data privacy can be found in our Data Protection Policy.