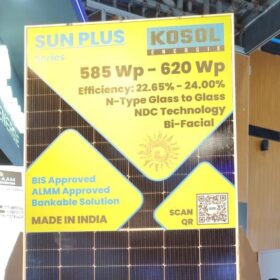

Budget expectations for solar manufacturing

The government should consider offering a 50% capital subsidy for setting up R&D and quality testing infrastructure within the manufacturing units and a 200% super-deduction for the R&D expenditure on new and clean solar technology development. Simultaneously, it should look at implementing tariff barriers on imports for at least four-five years.

Catalyzing the growth of rooftop solar in India

Challenges like frequent policy and regulatory changes, high capital costs, low awareness, non-uniformity in approval processes across states, restriction on net metering, and additional charges by DISCOMs need to be addressed for rooftop solar to take off in India.

Debunking feeder segregation

Feeder segregation, i.e., the installation of dedicated electricity supply lines for agriculture, is often celebrated as the solution to the electricity utilities’ pain point of free or highly subsidized electricity supply for agriculture. But does it address the root cause of the issue?

India’s path away from climate disaster lies in the rapid growth of renewable power

The nation is already firmly positioned to lead the world in the clean energy revolution. Consolidating this position would unlock significant economic growth and competitiveness by attracting domestic and foreign investment, creating jobs, and improving public health.

INR 2.0/kWh tariff is a new milestone in Indian solar PV history

The minimum solar tariffs discovered fell by 131.5% over the last five years, with an 18% drop achieved in the last five months alone.

Driving a just clean energy transition

Climate Policy Initiative and REConnect Energy have developed an innovative mechanism called Garuda to retire old, inefficient thermal plants with equivalent renewable capacity. The scheme proposes a blended tariff that would include the normal tariff for the new renewable energy plant plus the cost of decommissioning the old fossil fuel plant, while making the provision for green bonds to finance RE.

Rooftop solar market in 2020

It has been a rocky year for installers with issues like availability of modules from Chinese suppliers, restricted construction due to local lockdowns, and uncertainty over import duties. Going forward, the market could see a dramatic rebound if net-metering is allowed with a current cap of 1 MW and re-introduced in the states that have shifted to gross-metering.

Towards a distributed solar energy future

A study by Auroville Consulting assesses the techno-commercial impact of generating solar power close to the point of consumption. The study was undertaken on ten feeders of a substation in the Erode district of Tamil Nadu. The results indicated that 100% solar energy penetration, in energy terms, is not only possible but a winning proposition, especially for the distribution companies.

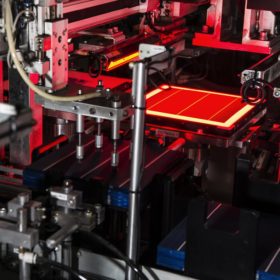

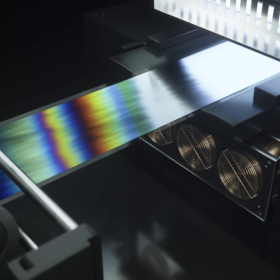

Conformity assessment of solar PV panels in India

Quality of testing is equally important even as new test labs come up for solar modules. Proper equipment selection and frequent calibration of equipment are prerequisites to ensure the credibility of the test results.

Manufacturing a green solar bounce in India

The nation must look at innovative PV technologies that are low-cost and can be applied in a vast range of new applications.